where domestic workers sleep

In Singapore, migrant domestic workers are required to reside in their employer’s home, where the living conditions can vary considerably. Current policy ambiguously states that employers are expected to provide ‘acceptable accommodation’, which is then not monitored by the state or employment agencies. Based on interviews with 45 different domestic workers between 2016 and 2017, 8 of whom were interviewed again more recently in 2020 and 2021, I worked with illustrator Gabi Froden (http://www.gabifroden.com/), to bring visibility to the spaces described by these migrant women.

-

on a balcony

-

in their own bedroom

-

in a store cupboard

-

under a table

-

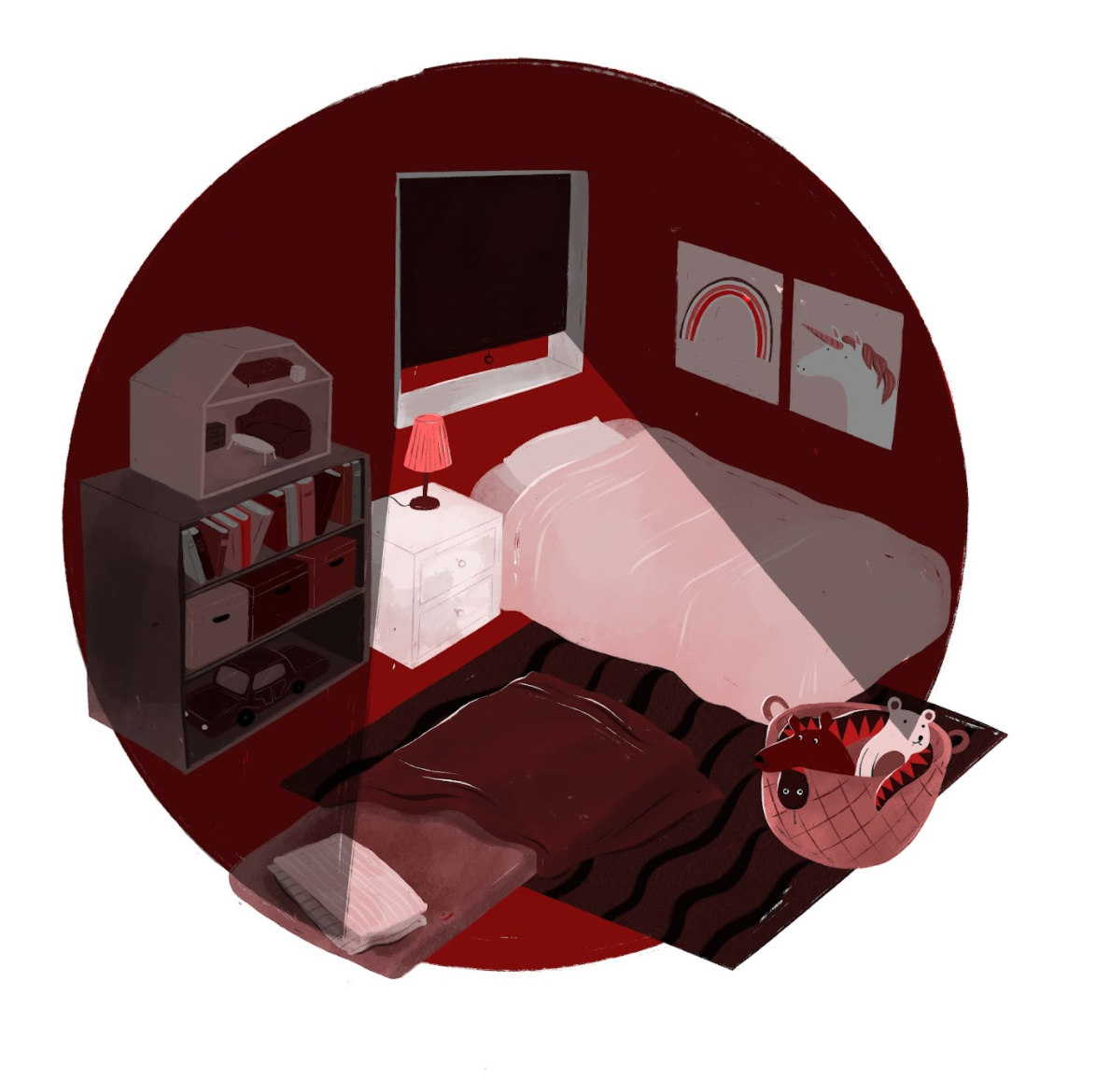

in a child's bedroom

-

on a sofa, in the living room

-

next to an elderly person

-

in a maid's room

-

on a balcony

A campaign for decent work

The interviews conducted reveal that there has been a lack of recognition that accommodation is not just a place to lay down and sleep, but a place of safety and comfort, where domestic workers can recuperate, recover (from work and if/when unwell), gain privacy, and relax when they are not working. Many domestic workers were interviewed were required to either share rooms with their employer’s children or elderly relatives, or to sleep in more public areas (in living rooms, storage cupboards, corridors, or kitchens). One domestic worker, Siti, described how she would move her thin mattress each evening to the floor of one of the children’s’ bedrooms, the living room, or the family office. Her possessions were stored in a small set of drawers in guest bedroom downstairs. She lived with the family for six years, sleeping with no privacy and unable to rest or recuperate when she was unwell. She explained that while her employer always said that she was “one of the family”, she could no longer believe her when she saw how they treated their new dog four years into her employment. She explained:

“Before the dog come, they are preparing a room for the dog … the food also, must eat drumstick and beef. Drumstick and beef! That’s when I’m thinking, I’m your maid, stay for four-years … You say you treat me like family but how come you treat the dog better than me?”

While some domestic workers had their own rooms and were very happy with their accommodation, many others had their own frustrations and felt as though they were infantilised, dehumanised, and treated with little respect. One domestic worker even described being forced to sleep on a sofa on the balcony of an apartment, barely protected from the elements. They stressed their daily bodily discomfort and the feeling that they were not seen as a human being. These illustrations quickly bring to light the diversity of domestic workers experiences and shed light on day-to-day challenges and exploitations embedded in this kind of live-in arrangement. They do so in a way that words alone cannot, and without compromising the anonymity of the domestic workers interviews, as photography would in this circumstance.

Subsequently, I have worked with the Humanitarian Organisation of Migration Economics to produce a policy briefing based on the findings from this research and our shared concern with the current policy wording. This forms part of the ILO’s Decent Work Campaign.